I decided that the best way to start the development of Infinity Gun would be with some paper prototyping. I knew that the first thing I wanted to create was an MVP, which stands for “Minimum-Viable-Product.” A Minimum-Viable-Product is essentially the product (In this case, my game) stripped down to its barest essentials. It’s the game without any of the extra visuals, stimuli, features, or gameplay complications, and it’s entirely meant to test one thing: Is the core gameplay engaging? Is it fun?

An MVP is important because it allows me to test my game idea in a way that I simply cannot in my head. It allows me to find edge cases and oversights in my game, and it helps me understand which parts are properly engaging. By cutting the game down to it’s absolute minimum set of features, you can find out whether the core gameplay is working, and whether the game’s core gimmick makes it fun. It would be way more difficult to find out why the foundation of your game isn’t working when it’s packed with content – this is the value of an MVP.

So to create my MVP, I boiled my game down to its bare essentials:

- I removed all enemy types. In my MVP, there is only a single, basic enemy type that will automatically shoot the player when the player steps in front of the enemy.

- I removed all gun variations. The gun in my MVP will only ever shoot a basic, single-shot, kill-on-impact bullet.

- I removed all special terrain features or obstacles. There are no crates that the player can push around, there are no pits the player can fall into, there are no laser-grid walls. The terrain is limited to the “Wall tile” and “Floor tile”.

- For the first prototype level, I even removed the enemy’s ability to move. They were restricted to waiting and turning. I did however end up implementing enemy movement in subsequent prototype levels.

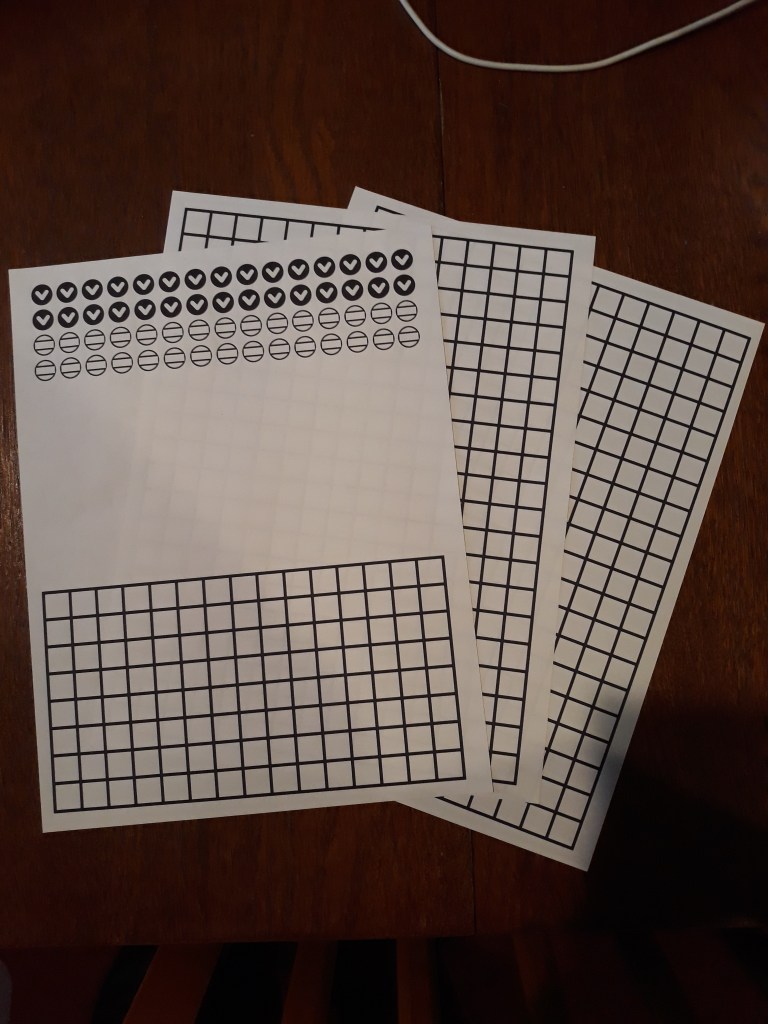

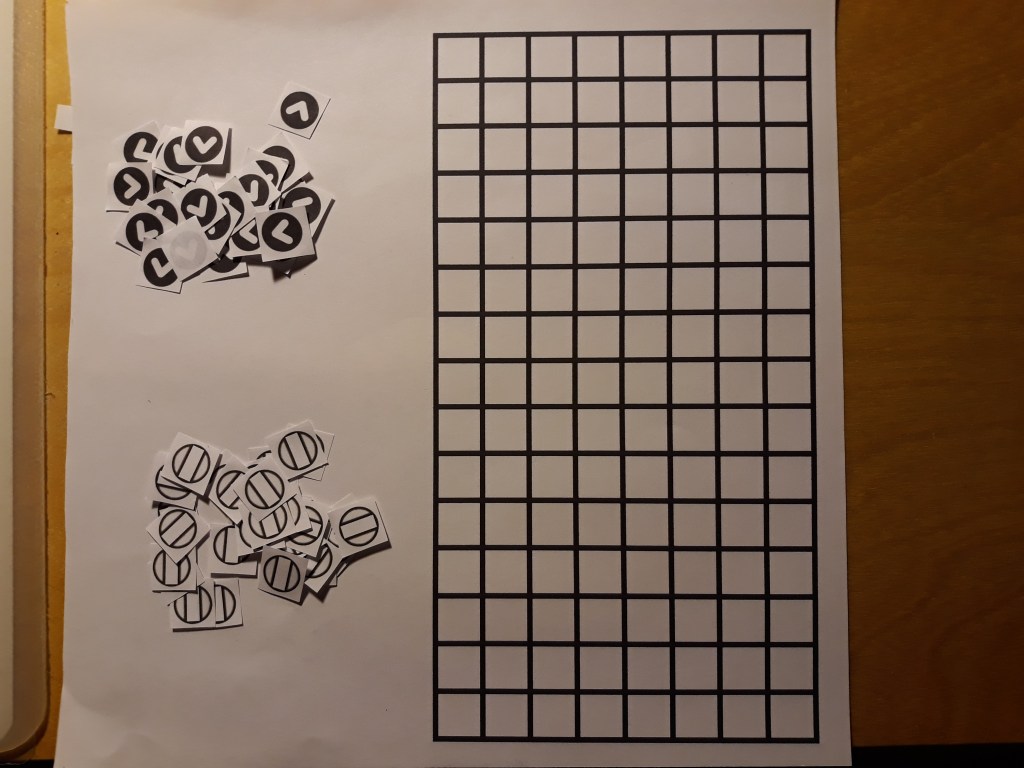

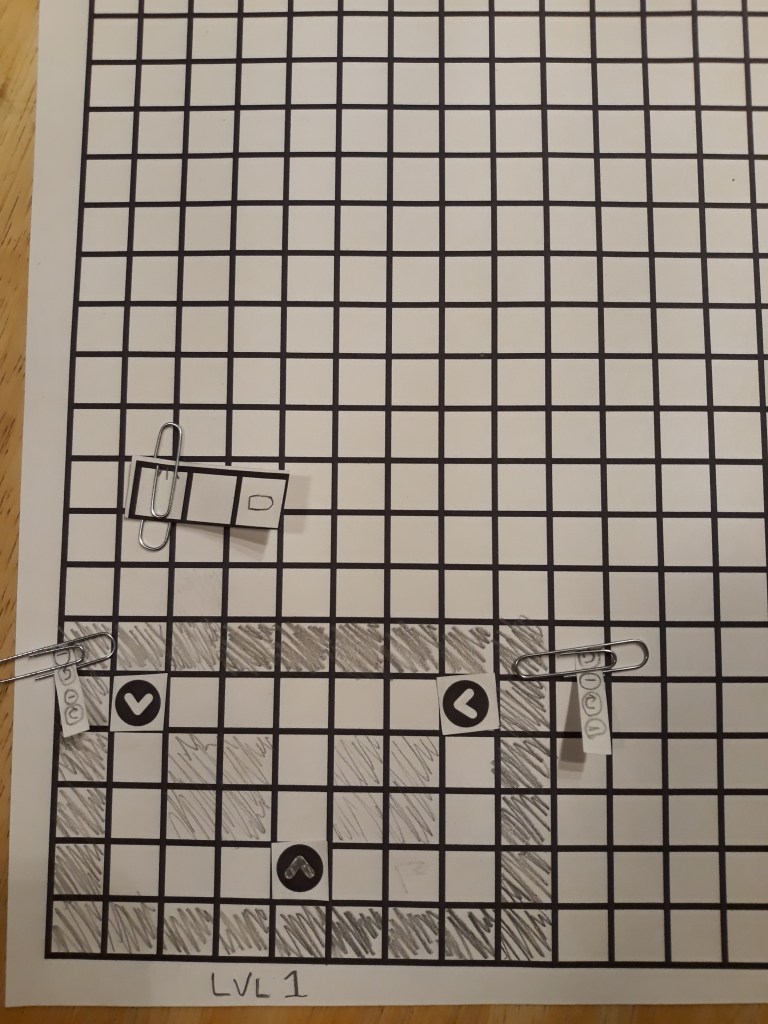

To create this MVP, I started by opening up Adobe Photoshop and creating my own grids and tokens. I used a grid on a piece of paper to create the layouts of my game levels (By filling in boxes to show where walls were), and created circular tokens with an arrow to show which direction the token is facing. Some of the grid paper would also be used to show the pattern in which the player’s gun fires. I also created some somewhat different circular tokens with a rectangle in the middle to be used as potential obstacles if I wanted to implement those in future prototype levels, but I did not end up using any of them.

I then created a couple of game levels, using small slips of paper and paperclips to show the programming of the enemies and what the stage the programming or gun pattern was on. I tested the game with both myself and multiple family members. However, I quickly realized that the pool of volunteers to help me test my prototype was quickly thinning out, since, with this testing taking place during the coronavirus pandemic, I was restricted to testing the game with only the people in my household.

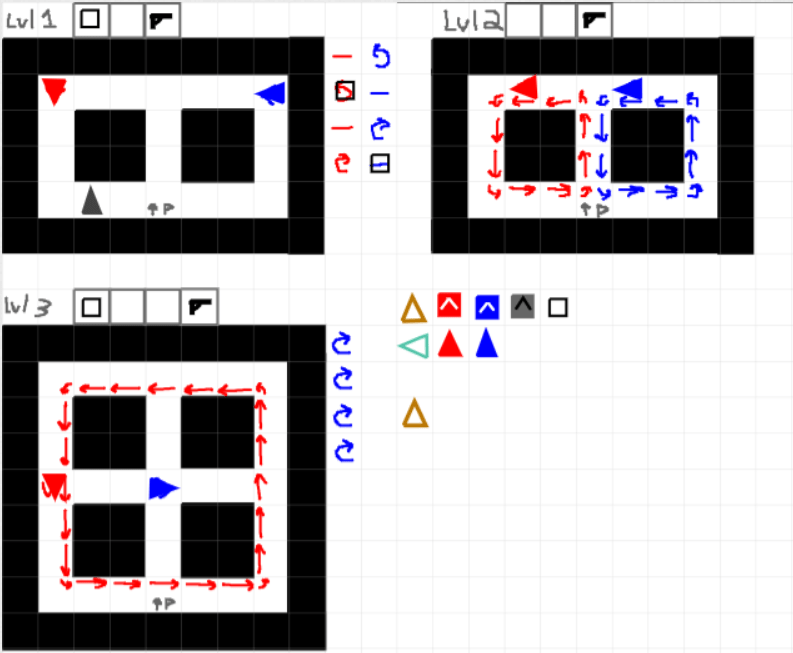

So, I decided to move my simple, manual prototype to a digital medium, where I might be able to test it with my friends as well as family.

I decided to use Roll20, which is a digital platform for playing tabletop role playing games such as Dungeons & Dragons. However, it was still perfectly usable for my purposes, as there were plenty of drawing tools that allowed me to easily replicate the levels from my paper prototype onto a digital medium.

Using both the paper prototype and the digital prototype, I tested my game over multiple weeks (When I wasn’t busy studying for exams). Sure enough, the testing let me find some important edge cases, and allowed me to find out what added and what subtracted from the gameplay experience. Some examples of what I found:

- The game works best when it is set in narrow corridors. Narrow corridors mean that the player is constantly in a state of danger, at least until they start taking out some of enemies. This is because by keeping the corridors tight, the enemies always have sight down long stretches of corridor, and combining this with the movement of the enemies around these corridors means that the player has to constantly keep moving between passageways that are just out of sight of the enemy, at least until a few of the enemies have been dispatched.

- There will be cases in which enemies will have to move through each other, and where enemies will have another enemy blocking their sight. This was a problem I didn’t think of when I was coming up with the idea of this game, but the problem did come up during testing. I decided that enemies should be allowed to move past eachother; However, enemies would also block eachother’s sight, which means that the player can use a different enemy as cover to slink past an enemy that is facing them.

- Certain level configurations are simply impossible. Because this is a game that tests puzzle-solving skills rather than reflexes or reaction times, there are certain level configurations that straight up simply cannot be solved – I have to make sure I test each one of my levels extensively so that I know they are solvable.

In the end, of course, there was one primary question all of this prototyping was meant to solve: Is the core gameplay fun? Thankfully, from both testing it with myself and with several others, I got a resounding yes. This was great; it meant that I now had a solid foundation on which to begin creating my game. The next step will be to start developing the game proper using the Unity game engine, by first implementing the basic game functions.